If you had grandfather or now more likely, a great-grandfather, who served in the British Army in the First World War 1914-18, it is now possible to research their service with most of the information digitised and available on-line.

The first place to start is with a good subscription to a genealogical site like Ancestry or Find My Past. I primarily use Ancestry and assuming that you have some basic details about your relative, the initial searches are quite simple.

There is a generic search tool for Military Records on Ancestry, make sure you click the UK and Ireland filter or it will give you lots of American records too.

If your relative’s surname is a common one e.g. Smith or Jones, you will need more information to input. Full Christian names and year of birth are a big help. Should you be searching for an uncommon or unusual name, sometimes you have to ‘think outside the box’ as there may have been a spelling mistake made over 100 years ago. As well as original spelling mistakes, there have also been spelling errors made in the digitisation process, but do not despair, patience is a virtue and I am always here to help if you contact me.

The Jewel in the Crown is to find a surviving Service Record. This will contain all of the information that you could possibly want. Unfortunately, many of the WWI Service Records for other ranks were destroyed during WWII, and those that have survived are often damaged and frayed around the edges. they are known by researchers as the Burnt Series.

If your relative was a Commissioned Officer – Second Lieutenant, Lieutenant, Captain, Major, Lt. Colonel etc. then those service records are all intact and available through The National Archives, usually at a cost.

This is the first page of my grandfather’s Service Record showing that he attested in September 1914 and added two years to his age!

The next record that I look for is a Medal Index Card (MIC). If a Service Record is not available, then the MIC can often give you a good starting point. It will give the soldier’s service number and his regiment/s, it will show the medals that he was awarded – if he doesn’t have the award of a 1914/15 Star, then you know that he didn’t serve overseas before 1st January 1916. It often gives the date of the soldier’s entry into a theatre of war and the location, and sadly, it will also record the death of the soldier or his discharge through serious wounds or sickness. There can often be abbreviations on the card such as KR (King’s Regulations), AO (Army Order), Class Z (The Army Reserve) – all of these abbreviations can be found on-line, or again, you can contact me for help.

My grandfather’s MIC shows his name, number, rank, regiment, the date he arrived in France, that he was discharged in April 1917, that he was awarded the 1914/15 Star, the British War Medal and the Victory Medal and a Silver War Badge (SWB) – see below – due to his wounds.

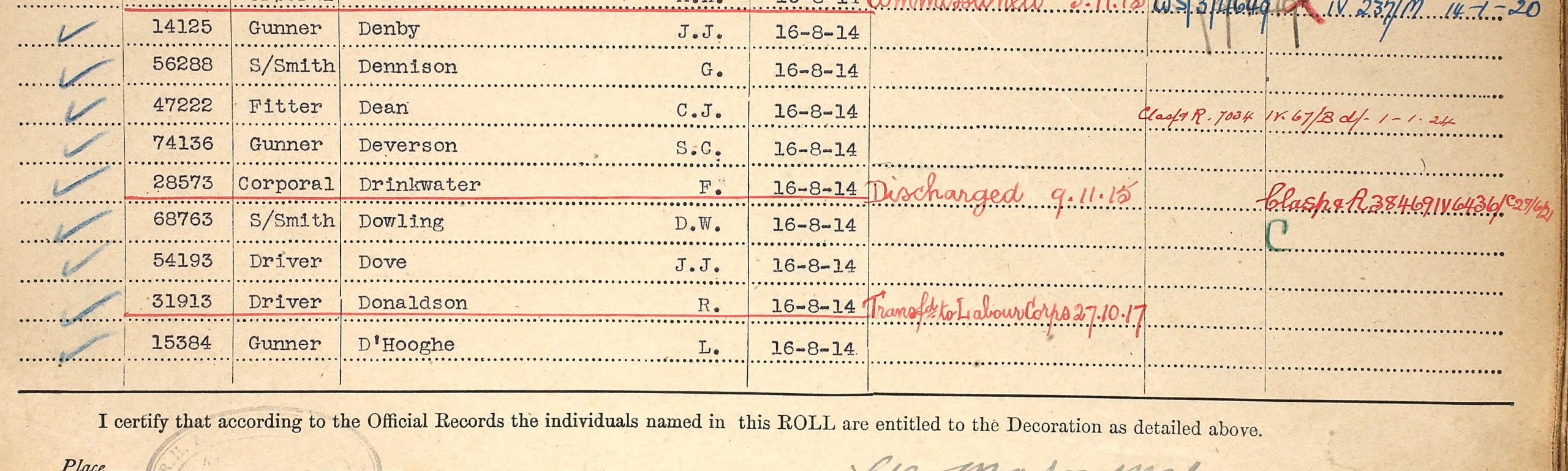

The next record I search for is the Regimental Medal Roll. This confirms the information found on the MIC, but can also add more specific information such as a regimental battalion number or if serving in the Royal Artillery, a battery number – this aids the search for War Diaries – see below.

Medal Roll for the Corps of Hussars, my grandfather’s regiment was the 20th Hussars. It confirms that he was discharged on 9th April 1917 under KR 392 xvi (King’s Regulations, paragraph 392, clause 16 – No Longer Physically Fit For War Service.)

If your ancestor was badly wounded, he would be awarded a Silver War Badge. This was worn on your civilian clothing and showed other people around you or at a job interview for instance, that you had served, done your bit, and were now discharged because of wounds.

Here is the SWB record for Herbert D’Hooghe. Discharged as above, KR 392 xvi.

In recent times, all of the surviving Pension Records have been digitised and these are available through an area of Ancestry, known as Fold 3. These of course, only apply to men who served, were wounded and survived. They can contain a treasure trove of post-war information and often detail the soldier’s battle against the authorities in an effort to secure a decent pension.

If your ancestor died during the Great War, either in action or from illness, you can search for his name and burial records through the Commonwealth War Graves Commission web site. This will give you details of his place of burial, the name of the cemetery and the grave reference. If the soldier’s body was not found or identified, it will give you the details of the memorial that he is remembered on.

Ancestry has the records of Soldier’s Effects available. This details a dead soldiers financial affairs e.g. back pay owing to him, or a War Gratuity payable to his family. It also shows who it was paid to and can often add other snippets of regimental information.

Soldier’s Effects record for Jack D’Hooghe showing that £1 – 2shillings and sixpence was paid to his father Thomas and later a War Gratuity for £8 – 10 shillings.

Many British soldiers were captured by the enemy during the war and became prisoners (POW’s). The International Red Cross provided a sterling service during the war in recording prisoners held by the Germans, and today, these records are available through the Red Cross web site.

POW record for Herbert D’Hooghe detailing where he was captured and the nature of his wounds.

If your curiosity extends to wondering what your ancestor did each day at the front, providing you have his battalion number, you can search for and read a day by day account of the battalion in the Battalion War Diary. These records are all on Ancestry.

Pre-war and post-war family records can be found in the 1911 and 1921 Census along with all birth, marriage and death records.

Finally for this article, it is also worth delving into the British Newspaper Archives – subscription required or drop me a line. The newspapers of the day can often turn up miraculous information that would otherwise have been lost in the mists of time.