In March 1915 at Neuve Chappelle, the British Army found that it could break in to the first German line of trenches but it could not break through or break out into the open country beyond.

German defensive tactics matured over the course of the war, but in essence, their tactical defence mechanism hinged on holding fresh counter attack units behind the front line. The pre-assault British bombardment not only damaged the German front line but it signalled exactly where the infantry assault would take place.

I have written on several occasions that there are only three certainties in life! – Death, Taxes and that the Germans will always counter attack to take back lost ground!

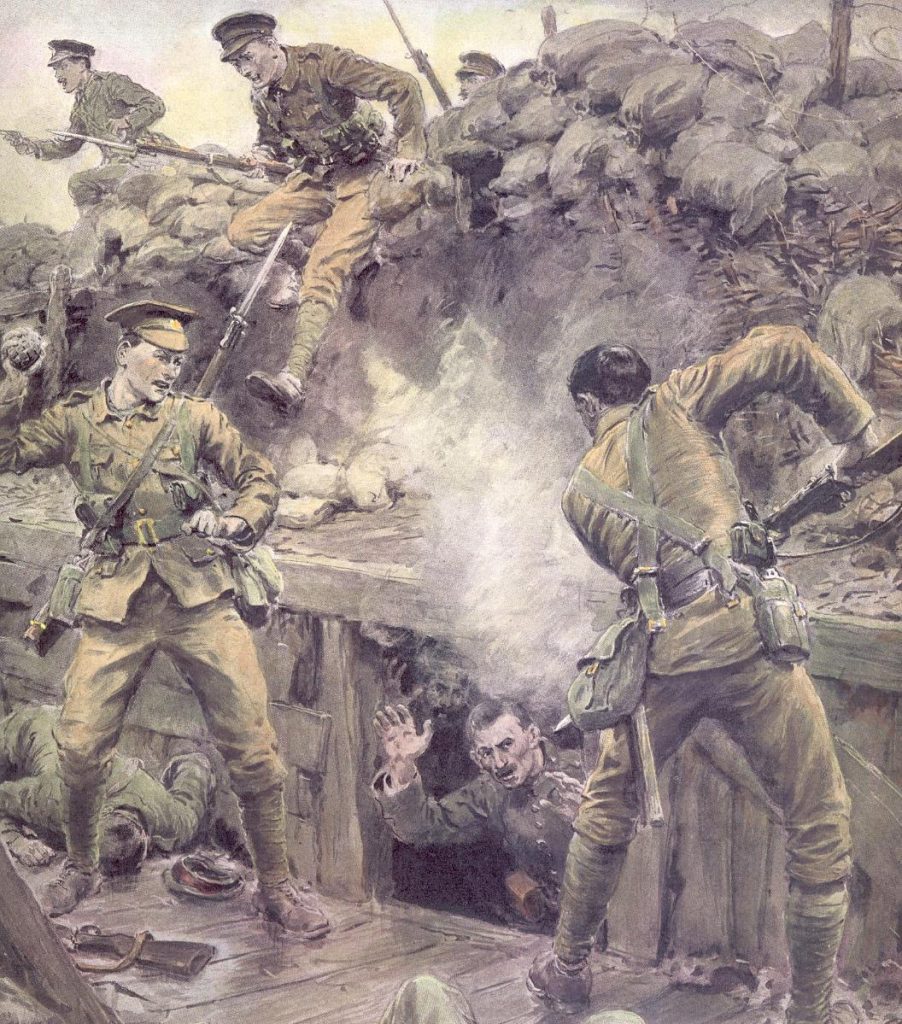

Typically on the Western Front, after a bombardment of several days, the infantry would ‘go over the top’ and those that had survived the machine gun fire in No Man’s Land would break into the German first line of trenches and set about consolidating their gains.

At this critical point in time, it was imperative that communication back to the British lines was established so that senior officers could launch a second wave of reinforcements to aid those men holding out in the German trenches. The survivors of the first wave would by now, be exhausted, and running short of ammunition and bombs (grenades).

The Germans were well aware of the vulnerability of the attackers at this point, and would put down a box barrage into No Man’s Land. This stopped British reinforcements from crossing to the support of the first wave and then launch their counter attack units who swiftly mopped up the surviving troops as they ran out of ammunition. Thus, the stalemate continued as those lucky enough to survive the counter attack, attempted, usually under the cover of darkness, to regain their starting trenches which they had left earlier that morning.

This inability to break the mass of trench lines on the Western Front became the number one problem that had to be solved if the war was to end in an Allied victory.

Many of you who have heard me talk, will know that I do not subscribe to the full ‘Butchers and Bunglers’ or ‘Lions Led By Donkeys’ theory regarding British tactics and senior leadership, but nor do I give full credence to the notion of a British Army ‘Learning Curve’. Yes, the British Army did learn to fight a new ‘all arms’ battle in 1918 when new technology – updated aircraft and tanks spring to mind – became available, but for me, the one charge that sticks time and time again against the senior British Officers in the Great War, is that of trying the same old thing over and over again, in the belief that you would eventually get a different outcome.

The story of the fighting at the Hohenzollern Redoubt in September and October 1915 is a prime example.

On September 25th 1915, the British 1st Army commanded by Sir Douglas Haig and under the overall command of Sir John French, launched the offensive that we know as the Battle of Loos. This was the biggest battle fought by the British to this point in time, with six divisions committed on the opening day in support of a much larger French offensive in Artois.

From Loos town in the south to the Hohenzollern Redoubt in the north, the opening assault tore large holes in the German front line positions after a substantial bombardment, and for the first time, the use of gas against the German defenders.

The Battle of Loos also saw the first use of Kitchener New Army divisions on the Western Front. These volunteers who had been civilians just one year before, acquitted themselves well in the opening stage of battle alongside the London Territorials of 47th Division at Loos and the Regular army troops of 1st, 2nd and 7th Divisions at Hulluch and the Quarries.

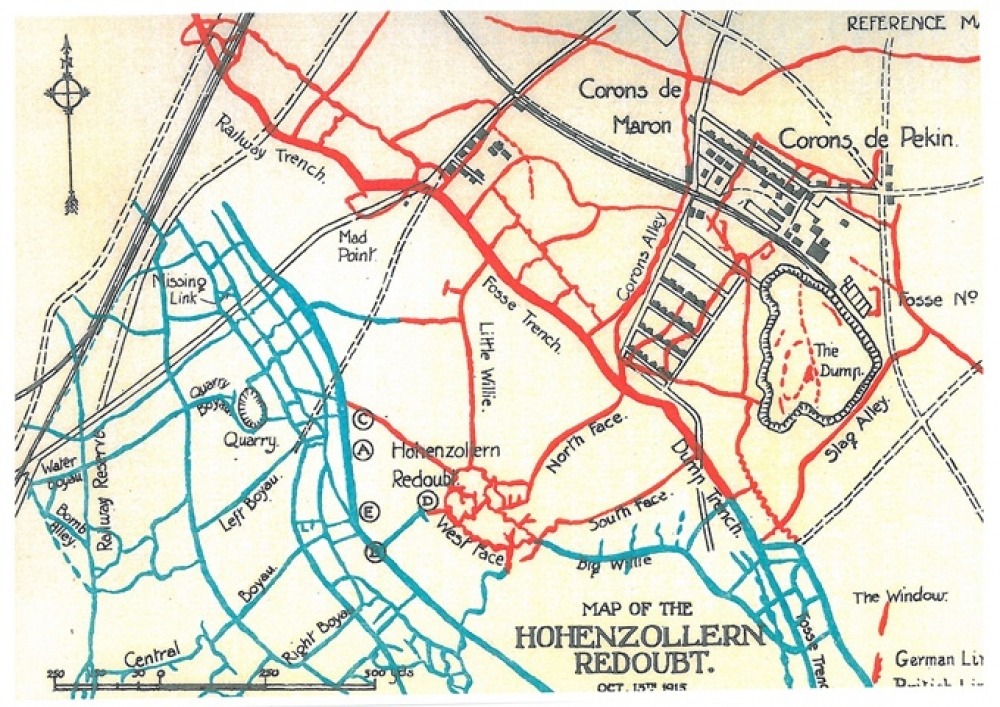

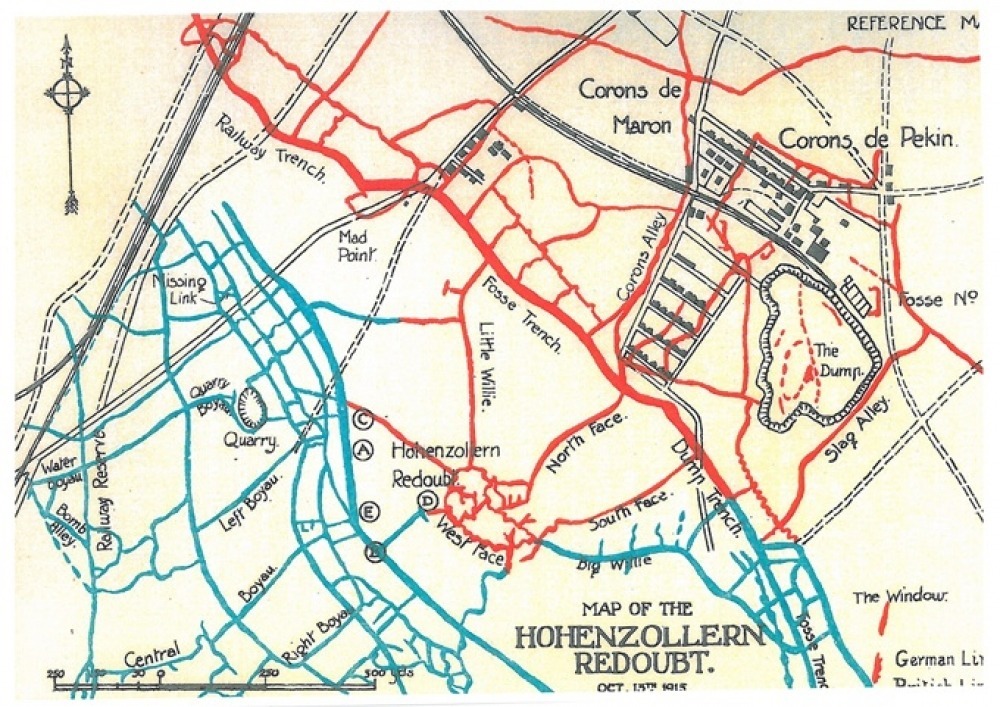

The first two Kitchener divisions in battle were both Scottish, namely the K1 9th (Scottish) Division and the K2 15th (Scottish) Division. It was the 9th Division that assaulted the Hohenzollern Redoubt and whilst taking heavy casualties as they crossed No Man’s Land, the kilted Scots stormed the Redoubt and captured not only the first trenches, West Face, South Face, North Face, Little Willie, Big Willie and Fosse Trench, but troops penetrated as far as Fosse 8 (the coal pit shaft head) and the Dump. See map below.

Success had also happened further south, with the Londoners taking Loos village after a stiff fight and advancing towards Hill 70. It was at this point on the critical first day, that everything started to go wrong. Haig had warned French that he would need his reserves within three hours of battle commencing, but Sir John French as C-in-C, had decided to keep the 21st and 24th reserve divisions under his own command. French, located well in the rear of battle, did not receive news as communication broke down and when Haig needed his reserves to reinforce success at Loos and at the Redoubt, it was found that the reserves were up to five miles away and as they eventually marched towards the front, their route was hampered by the medical chain moving the wounded in the opposite direction.

By the time that the first of the reserve battalions arrived at the front, they were already tired, disorganised and hungry and were then thrown piecemeal into the battle, including the 8th Lincolns who suffered heavy casualties at Bois Hugo.

The Scottish troops holding out in the Hohenzollern Redoubt were by afternoon, desperately in need of support and supplies of ammunition, food and water. Bravely, they held out against repeated German counter attacks all through the 26th and 27th of September, but yard by yard, they were forced back until the Germans had control of most of the Redoubt once again, but with the British remaining in Big Willie Trench and the southern portion of Fosse Trench. (Blue on the map below).

When war was declared in 1914, many Regular Army battalions were stationed in the Empire and as Territorial battalions arrived in Malta, India, the Caribbean etc. so these Regular Army battalions returned to the UK and were hastily formed into three new divisions, the 27th, 28th and 29th.

The 29th Division went to Gallipoli where they landed at Helles in April 1915 and the 27th and 28th Divisions arrived on the Western Front in March 1915 where they fought in the 2nd Battle of Ypres, and for the 28th Division, they then found themselves at Loos in support of the 9th (Scottish) Division.

Severely depleted from their action, the Scots handed over their tenuous gains to the 28th Division, the positions being taken by units of the 85th Brigade.

Fierce fighting continued for the next three days with German counter-attacks slowly and painfully retaking trenches. At the end of 30th September the British occupied the West Face of the Redoubt and Big Willie Trench. The Germans controlled most of Little Willie Trench, threatening the north flank of the Redoubt. On the night of 30th September/1st October 84th Brigade relieved 85th Brigade. German observation of this relief from the heights of the Dump was total and the new British occupants were subjected immediately to strong bombing attacks. The British held on – but only just.

That night, they would attack to improve their hold on the German trenches. The plan was risky, involving no artillery bombardment. The attacking force captured parts of Little Willie Trench but could advance no further. German retaliation was swift; artillery subjected the Redoubt and Little Willie to regular and heavy trench mortar fire. A German bombing attack retook Little Willie Trench, followed by the loss of the Chord and West Face. Other than a small section of Big Willie Trench, the British were for the most part back in their original lines.

The blood-soaked redoubt would have to be assaulted again, this time by additional battalions of the 28th Division, the 1st KOYLI and 2nd East Yorkshires would attack the redoubt frontally, leaving the 2nd King’s Own to capture and consolidate Big Willie Trench. The optimistic plan depended on darkness providing the assaulting parties with the necessary element of surprise. Even then, the British would be advancing into a tumbled maze of trenches. The assaulting troops had no idea what they would be facing; there had been no time to reconnoitre the position and once again, the attack, resulted in a bloody disaster.

I will take you back now to my earlier comments. Why at this point, did the Senior British Command, decide to throw a third division into this maelstrom? And, after the 9th Division and the 28th Division had failed to take and hold the Redoubt, why did they think that the 46th Division could capture the Redoubt when attacking with only one Brigade? (Two battalions of 137 Brigade and two battalions of 138 Brigade).

The 46th (1st North Midland) Division had been the first full Territorial Force division to arrive on the Western Front in February/March 1915. It’s ORBAT (Order of Battle) was:

137th (Staffordshire) Brigade – 1/5th South Staffs, 1/6th South Staffs, 1/5th North Staffs and 1/6 North Staffs.

138th (Lincs and Leics) Brigade – 1/4th Lincolns, 1/5th Lincolns, 1/4th Leicester’s and 1/5th Leicester’s.

139th (Sherwood Foresters) Brigade – 1/5th SF, 1/6th SF, 1/7th (Robin Hoods) SF and 1/8th SF.

The 1/1st Monmouth’s were the 46th Divisional Pioneers.

The 46th Division was commanded by Major General The Hon. Edward James Montagu-Stuart-Wortley. He was a popular commander and well respected by his troops. We should also note at this point, that he was well connected in upper class circles and was a personal confidante of King George V and a good friend of Sir John French.

When we consider the 46th Division’s attack at the Redoubt on 13th October 1915, we must also remember that they were not attacking in isolation. To their right (south) the 12th (Eastern) Division would attack the Quarries – but note that the left hand battalion of 12th Division (7/Suffolks) was not in touch with the right flank battalion of 46th Division (1/5 South Staffs) – this gap in the attacking line allowed the defenders to enfilade the right of the South Staffs and the left flank of the Suffolks.

To the 46th Division’s left (north), the 2nd Division would attack, with the 1/Queen’s specifically tasked with neutralising the German machine gun emplacement known as Mad Point. That this did not happen, added hugely to the losses suffered by the Lincolns and Leicester’s.

The scene is now set. The chain of command – Sir John French as C-in-C, Sir Douglas Haig as 1st Army Commander, Lt. General Richard Haking as Corps Commander and Major General Montagu-Stuart-Wortley as Divisional Commander were now all under pressure to perform.

French, who was aware that his job was at stake, needed a victory, Haig, who was wheedling behind the scenes to replace French, was pressuring Haking and Montagu-Stuart-Wortley to prepare the plan of attack.

Montagu-Stuart-Wortley favoured a methodical approach and made constructive proposals which were rejected. Haking insisted upon a daylight full frontal assault against the entrenched German positions believing that the weight of artillery support and the use of gas would aid the attack – in essence, a complete repeat of September 25th which had failed.

The 1st Army artillery support on the 13th October consisted of 56 Heavy Howitzers, 86 Field Howitzers, 19 Counter Batteries to suppress German return fire and 286 Field Guns, although I must point out that the Territorial batteries of 46th Division were still armed with the obsolete 15 pounder, and we should also note that the 46th Division’s North Midland Heavy Battery RGA had been withdrawn from the division the previous April.

The artillery support was not just for the 46th Division, it also supported the 12th and 2nd Divisions over a combined front of 5,480 yards. This equated to a gun every 12.3 yards for the two hour bombardment which is about half the density that had shocked the Germans at Neuve Chappelle six months earlier, although that bombardment lasted only 35 minutes. We can therefore, conclude, that the artillery support for the impending attack was wholly inadequate, and once again the PBI (Poor Bloody Infantry) would pay the price for their efforts in warfare for which the nation was not adequately supplied or prepared.

Sir John French was pushing daily for an early resumption of the attack, he was now coming under intense pressure from the politicians in London, and he even suggested an attack on the 10th without the use of gas. This was rejected by Haig, whose diary entries suggest that he knew the artillery strength was inadequate, and therefore, the use of gas was imperative.

Eventually a plan was agreed for 13th October:

12 noon – artillery bombardment begins (Including smoke – note firing smoke reduces the weight of the bombardment)

13.00 – Gas released.

14.00 – Artillery bombardments ends.

14.05 – Infantry attack commences.

The 46th Division assault would see four battalions attack in the first wave. From left to right (see map below – which clearly shows the gap between 1/5 S. Staffs and 7/Suffolks) 1/5th Lincolns, 1/4th Leics, (138 Brigade) and 1/5th N. Staffs and 1/5th S. Staffs (137 Brigade).

It immediately became apparent to observers that the artillery bombardment was having little effect on the defenders. The 1/5th S. Staffs war diary records; “….the bombardment did not appear to effect the South Face or the Dump Trench….”

The war diary of 1/4th Leicester’s states; “At 1.50pm the smoke and gas stopped and the enemy began to snipe the top of our parapet with machine guns.”

The 1/6th S. Staffs war diary very sadly notes that; “As the artillery preparation grew more intense and the time for the advance approached, the enemy machine gun fire was playing with such effect upon the assembly trenches that the C.O. was compelled to report to Brigade the apparent futility of any movement.”

The 1/4th Lincolns would advance in support of the first wave and they were taking accurate artillery fire and casualties from the Germans as they waited in the support trenches, the 1/4th Leicester’s noted that the smoke and gas appeared to stop ten minutes too soon, and that this would leave the attackers fully exposed.

Nevertheless, the whistles blew and the leading wave left their trenches as planned. The 137th Brigade Diary states; “The attacking troops left their trenches five minutes before Zero, and started with the greatest confidence, but immediately began to suffer heavy loss from terrific machine gun and rifle fire. The great mass of this fire came from a number of machine guns in concealed shelters both near the foot of the Dump and in the south west and south east sides of the Corons [Corons being the little miners cottages that had been used by the Germans – Ed], and also from parties of Germans who had held out stubbornly in Little Willie and Dump trenches.”

The account continues and notes that the 1/5th N. Staffs were “practically annihilated.” The Lincolns and Leicester’s crossed No Man’s Land with fewer casualties than the Staffordshire’s, but when they reached the German positions, they then came under murderous fire from the Dump and from Mad Point, which had not been suppressed by 1/Queen’s as planned.

Three of the four battalion commanders were casualties and the loss amongst junior field officers was very high. Men of the Lincolns and Leicester’s did occupy parts of the Redoubt and the North Face, but Big Willie and Little Willie trenches [Named after the Kaiser and his son – Ed] were still in German hands. The battle continued as a series of hand grenade actions as small partes tried to consolidate their position.

The 139th (Sherwood Forester) Brigade had not taken part in the initial attack, although the Forester’s bombers had attacked with the first wave. The Foresters in rear support trenches were under continuous fire and as the afternoon wore on, Companies were ordered forward to try and support the surviving troops in the Redoubt, but crossing No Man’s Land under fire was treacherous, not to mention the amount of Scottish and 28th Division corpses that were lying there from the fighting over the previous eighteen days.

During the night of 13th/14th October, men of the 7th and 8th Foresters dug a new communication trench under fire so that supplies of ammunition and rudimentary grenades could be supplied to the defenders in the Redoubt. (see map)

Over the next 48 hours, the surviving Lincolns, Leicester’s and Foresters stubbornly held their ground and during this period, Captain Charles Geoffrey Vickers of the 7th (Robin Hoods) Sherwood Foresters, was awarded the Victoria Cross for his stubborn defence of the captured trenches.

His VC citation reads; “When nearly all of his men had been killed or wounded at the Hohenzollern Redoubt, and with only two men to hand him bombs, he held a barrier for some hours against heavy German attacks . He then ordered a second barrier to be built behind him to ensure the safety of the trench in the full knowledge that his own retreat would be cut off. By the time he was finally severely wounded, the barrier was complete and the situation saved.”

Remarkably, Vickers, with some thirty separate wounds survived the war to lead a successful life and be awarded a knighthood.

Time and space does not allow a full description of the fighting in the Redoubt but I hope I have given you a flavour of the terrible conditions that the 46th Division had to bear on this day? And the inadequate artillery support that was available.

The divisional casualties were as follows.

137 (Staffordshire) Brigade Officers Other Ranks Total

68 1,478 1,546

138 (Lincs and Leics) Brigade 64 1,476 1,540

139 (SF) Brigade 25 405 430

Divisional Troops 23 224 247

Total 180 3,583 3,763

Postscript – The attack had been another bloody disaster. The overall failure of the Battle of Loos led to the sacking of Sir John French and his replacement as C-in-C by Haig in December 1915. Much of the failure was also levelled at Haig, who passed the blame down the line of command.

Haig made several diary entries casting quite a slur on the brave lads of the 46th Division. He also commented that he didn’t think Montagu-Stuart-Wortley was fit to command a division, and this undoubtedly stems from Montagu-Stuart-Wortley’s letters to the King after the battle in which he undoubtedly criticised Haig.

Haig would get his revenge the following July 1st when the 46th and 56th Divisions were given the impossible task of capturing the village of Gommecourt on the opening day of the Somme offensive. Despite some 57,000 casualties on this day, only the 46th Division faced a Court of Enquiry and as the token scapegoat for the disaster of this day, Montagu-Stuart-Wortley was relieved of his command. [I give a talk on this subject that some of you will have heard – Ed]