This was a bespoke tour to the Western Front that I organised for the grandson of Andrew Shaw. I can organise custom tours on request, please contact me for any enquiry.

Below is in HTML format. This document is available in PDF format here

FOLLOWING IN THE FOOTSTEPS TOUR

8TH – 12TH JULY 2018

2740 PRIVATE ANDREW SHAW

THE NEWFOUNDLAND REGIMENT 1916-1918

LEST WE FORGET

- The 1st Battalion The Newfoundland Regiment.

- Raised by a Patriotic Committee at the Church Lads Brigade Armoury in St John’s on 21 August 1914. A training camp was established at Pleasantville.

- The first five hundred men (known as the ‘blue puttees’ from an item of uniform with which they had been issued) sailed for England on the ship ‘Florizel’ on 4 October 1914.

- 27 subsequent drafts were sent from Newfoundland to bring the battalion up to strength and after it sustained casualties.

- The five hundred landed at Portsmouth on 20 August 1914 and went to Pond Farm Camp, Aldershot. The battalion moved to Fort George at Inverness on 7 December 1914.

- On 19 February 1915 the Newfoundlanders moved to Edinburgh Castle for guard duties.

- The battalion moved to Stobs Camp near Hawick on 11 May 1915 and on 2 August 1915 moved to Badajoz Barracks at Aldershot.

- On 19 August 1915 the battalion sailed from Devonport aboard the liner ‘Megantic’ for service at Gallipoli. Going via Malta and Lemnos, the battalion disembarked at Alexandria in Egypt on 1 September. It went to Abbassia Barracks and thence to Polygon Camp.

- On 13 September 1915 the battalion returned to Alexandria and boarded the ‘Ausonia, which took it to Mudros, the advanced base for operations at Gallipoli, where it arrived five days later. The men then trans-shipped to the ‘Prince Abbas’ and disembarked at Kangaroo Beach at Gallipoli on 20 September 1915.

- The battalion now came under orders of the 88th Infantry Brigade of 29th Division.

- With this brigade the battalion saw action in the following engagements, in addition to having much time in holding front line trenches while there was no major, named battle:

- Gallipoli

- The battalion’s transport section was sent to join the Western Frontier Force in the western deserts of Egypt between November 1915 and February 1916

- Somme, 1 July 1916: in making an attack near Beaumont-Hamel on the first day of the Battle of the Somme, some 790 officers and men of the Newfoundland Regiment went into action. Of these, no fewer than 272 lost their lives; a further 11 officers and 427 men were wounded, making in all 710 of the 790.

- Somme, 12 October 1916: the battalion attacked near Geudecourt in a later phase of the Battle of the Somme.

- Operations near Sailly-Saillisel, 26 February to 3 March 1917.

- Monchy-le-Preux, 14 April 1917, during the Battle of Arras, and further operations at Les Fosses Farm on 23 April.

- On 28 September 1917 the regiment was granted a “Royal” prefix, becoming the Royal Newfoundland Regiment.

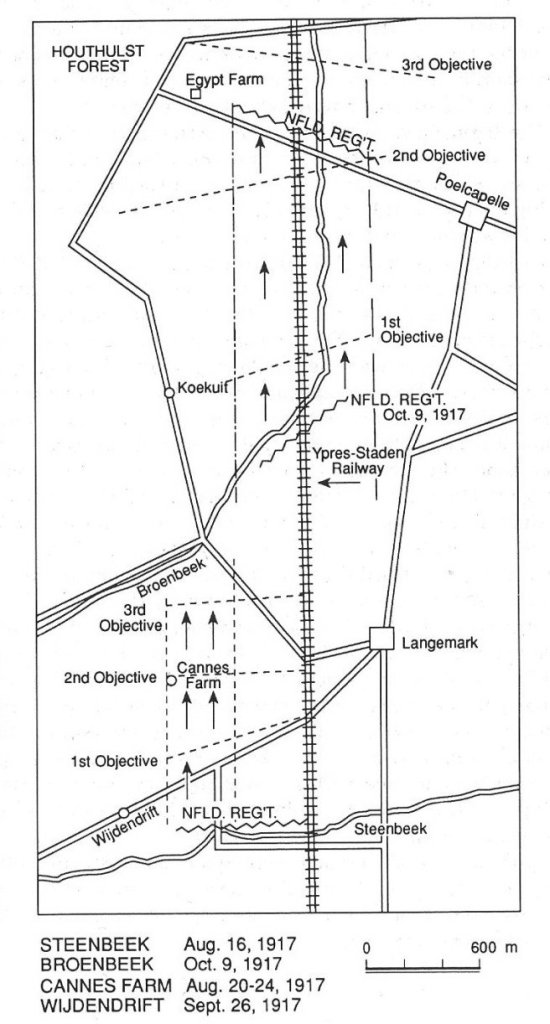

- The Third Battle of Ypres, 1917, in which the battalion was in action in an attack from the Steenbeek to Cannes Farm near Langemarck, 16-24 August 1917, and from the Broenbeek to near Poelcapelle, 9 October 1917.

- The Battle of Cambrai, starting 20 November 1917, on which the battalion advanced from near Villers-Plouich to Marcoing and Masnieres.

- The Battle of the Lys, 10-15 April 1918 during which the battalion was in action in the vicinity of Bailleul.

- Casualties had now stripped Newfoundland’s ability to maintain the battalion at full strength. In consequence it left the 29th Division and became ‘lines of communication troops’.

- After going at first to camp at Etaples, the battalion was assigned to guard duties at the British General Headquarters at Montreuil-sur-Mer, being based at Ecuires in order to do so.

- On 13 September 1918 the battalion moved to Wormhoudt where it was placed under orders of the 26th Infantry Brigade of 9th (Scottish) Division.

- The battalion took part in the final battles in Flanders, in the areas of Bellewaarde, the Keiberg spur, Ledegham and Vichte.

- The division was selected to advance into Germany as part of the Army of Occupation and commenced its move on 14 November. The Newfoundlanders crossed Belgium and entered Germany on 4 December 1918. After forming part of the Cologne garrison it moved in February 1919 to Rouen for POW guard duties.

- The battalion landed back in England and went to Hazeley Down Camp near Winchester in late April 1919. It took part in the London Victory Parade on 3 May 1919. Large drafts finally returned home in the May-July 1919 period.

(Info from longlongtrail.co.uk)

2740 Private Andrew Shaw – Timeline of Service.

He left his job at the Dominion Iron and Steel Company to join the Newfoundland Regiment on May 12, 1916. Andrew’s draft embarked aboard the troop ship S.S. Sicilian at St. John’s on July 19 1916 and landed at HMS Vivid Naval Base, Devonport, England. The troop continued their journey to the training base at Racetrack Camp, Ayr, Scotland. (The 2nd Battalion – Established at Ayr racecourse camp in early 1915, with the men being billeted at Newton Primary School. The battalion acted as a training unit, supplying drafts to the 1st Battalion.)

He first saw active duty on October 3, 1916, when he was assigned to the 1st Battalion Newfoundland Regiment under the command of British Expeditionary Forces – 88th Infantry Brigade in 29th Division. He embarked Southampton for Rouen, France and joined the regiment on October 14, thus missing the fighting on the Somme on July 1 and on October 12.

In November 1916, he was admitted to 1 Stationary Hospital and transferred to 51st General Hospital on December 12 at Rouen. He was discharged and assigned to Rouen base depot on December 19. He rejoined his battalion on January 17, 1917.

Andrew would undoubtedly have seen action at Sailly-Saillisel in February/March 1917 and at Monchy Le Preux in April 1917 as part of the battle of Arras.

During the summer of 1917 the battalion moved northwards to Belgium where it took part in the battle of Langemarck 16-18 August 1917. This was a phase of the 3rd Battle of Ypres – better known as Passchendaele. However, Andrew had already received a gunshot wound to his right leg during the early stages of the Battle of Langemarck on August 13, 1917.

He was transported by stretcher bearers to the nearest Field Ambulance and subsequently evacuated to the 3rd London General Hospital, Wandsworth, England aboard the hospital ship HMS Brighton on August 17, suffering from inflammation of the connective tissue in his right leg.

Records show that Private Shaw spent three months recovering from his wound. He was granted furlough on October 17 and he was re-assigned to H Company at Ayr, Scotland for strengthening and conditioning, thus missing the fighting at Cambrai in November 1917.

On February 3, 1918, he received orders to re-join the 1st battalion Royal Newfoundland Regiment.

He left for Southampton on February 3 and arrived at the front on February 15, 1918.

For the next two months the Regiment fought to hold defensive lines against a German Army determined to carry out a massive spring offensive along the Western Front in the hope of breaking the Allied Resistance. The battle of the Lys, April 10-15 1918 was the second phase of the German Spring Offensive.

Records indicate that on April 4, 1918, Private Shaw —along with approximately 150 other soldiers —went missing in action. It was assumed that they were either killed, wounded, or taken prisoner in the vicinity of Bailleul.

Several military records indicate that Private Shaw was reported missing on April 12, 1918, including Payroll and Daily Order papers. On May 21, both the Evening Telegram and St. John’s Daily News reported that Private Andrew Shaw was wounded and missing in action.

On May 15, a letter from a Hannover prison camp arrived at the Newfoundland Contingent Office in London from Private Andrew Shaw.

On June 12, 1918, Extract from Casualties, London report exciting news about Private Shaw, “Previously reported missing, 12/04/1918 now reported wounded (Leg) and Prisoner of War in enemy hands. #2740 Private Andrew Shaw getting better slowly.”

Due to the nature of his wounds, in September 1918, the Newfoundland Contingent is informed that Private Andrew Shaw’s name will be placed on the list for recommendation to the Medical Commission which examine Prisoner of War for repatriation or transfer to a neutral country and the decision to release Private Shaw rests with the Commission and not with the British Authorities. Private Shaw was subsequently repatriated to the UK where he recovered from his wounds and was demobilized in July 1919.

He married Mary Stanford of St. John’s on June 15, 1921. Andrew and Mary lived at 22 McKay Street, St. John’s and had nine children.

He spent the final two years of his life at St. Patrick’s Nursing Home on Elizabeth Avenue. He passed away on April 10, 1976, and was laid to rest at Holy Sepulchre Roman Catholic Cemetery, Topsail Road, St. John’s.

Caribou Memorial at Masnieres

As well as following in the footsteps of Andrew Shaw, we will take a look at several other sites of interest in both France and Flanders.

SUNDAY 8TH JULY

Leave Welbourn, Lincolnshire and head for Ypres (Ieper), Belgium via Eurotunnel.

MONDAY 9TH JULY

Klein Zwaanhof Farm, Kleine Poezelstraat, 8904 Boezinge. – This info-point covers the northern part of the old Ypres Salient from the Ieper-IJzer Canal in Boezinge to Wieltje. It is located in a former farmhouse, which was rebuilt after the Armistice on the site of Klein Zwaanhof along the road known as Kleine Poezelstraat. During the war, this farm was more or less in the centre of the northern sector of the salient. It was here from 22 April 1915 onwards that the fiercest fighting in the Second Battle of Ieper took place.

Visit to Yorkshire Trenches.

Langemarck – August 1917. Andrew Shaw’s first wounding at the Steenbeek.

On Aug. 8, 1917, the 29th Division moved into reserve to take over the line from the Guards Division, north of the Staden railway line. The attack was set for Aug. 13 but was delayed because of heavy rains. On Aug. 15, the 88th Brigade moved into line for the assault the next day. The approach to the start line was dangerous and slow due to the rains turning the mud into a swamp.

The 88th Brigade was to advance along the Ypres – Staden Railway, with the Hampshires next to the railway line and the Essex Regiment in support. The Newfoundlanders were on the left of the Hampshires, with the Worcesters in support. The 87th Brigade was on their left. This battle was to become known to the Newfoundlanders as the Battle of Steenbeek.

The objectives were marks on the map – Blue, Green and Red Lines. The first line, the Blue line, was just beyond the road from Langemark to Bixschote and level with Langemark. The Green or second line was about five hundred yards further on, while the Red line or the final objective of the attack was a couple of hundred yards short of the Broenbeek , another stream running across the battlefield. The advance covered about 1500 yards in all.

The Regiment approached the forward trenches on the night of Aug. 15. They spent a miserable time in water-filled shell holes and trenches, which gave little protection from shelling or weather. During the night, bridges were placed across the stream and the start line was marked with tape on the far side.

At 4:45 A.M., Aug. 16, 1917, the creeping barrage started. B and C Companies crossed the bridges and took their places on the taped lines.

A and D Companies followed. An enemy counter barrage did little damage. The companies moved steadily forward. The main obstacle was the machine gun fire from concrete emplacements. These were skilfully silenced by the troops. Within the hour, B and C Companies were on the Blue Line and A and D Companies passed through taking the lead in the advance to the Green line. The advance started on time behind the creeping barrage and by 7:45 A.M., the Regiment reached their objective on schedule. This had been a difficult passage due to the bog which was now a morass of mud from the rain and shell fire. The Worcester’s now passed through the Newfoundlanders, and behind the timed barrage; they advanced to the Red Line, which was the objective of the day. The Essex and Hampshire’s on the right, while first troubled by enfilade fire from across the railway embankment, nevertheless, reached their objectives on time.

Early in the afternoon the enemy was seen grouping for a counter attack. They were dispersed by machine gun fire and accurate artillery strikes. The Newfoundlanders dug in and strengthening their line, such as it was, in the muddy battlefield. During the day, they were subjected to artillery fire from the Germans and strafing from enemy aircraft.

On the left, the 87th Brigade was equally successful in capturing all their objectives. The 86th Brigade relieved the 87th and 88th Brigades and was able to exploit the gains made so far, capturing posts toward the Broenbeek. The advance of the 29th Division was the only attack that day that reached and held all its objectives. The centre and the right made little gain against a determined foe and horrible ground conditions.

Visit to the German cemetery at Langemarck.

Visit the tank memorial at Poelcapelle.

Visit to Tyne Cot cemetery.

It is now the largest Commonwealth war cemetery in the world in terms of burials. At the suggestion of King George V, who visited the cemetery in 1922, the Cross of Sacrifice was placed on the original large pill-box. There are three other pill-boxes in the cemetery.

There are now 11,961 Commonwealth servicemen of the First World War buried or commemorated in Tyne Cot Cemetery of which, 8,373 of the burials are unidentified.

The TYNE COT MEMORIAL forms the north-eastern boundary of Tyne Cot Cemetery and commemorates nearly 35,000 servicemen from the United Kingdom and New Zealand who died in the Ypres Salient after 16 August 1917 and whose graves are not known. The memorial stands close to the farthest point in Belgium reached by Commonwealth forces in the First World War until 1918.

The memorial was designed by Sir Herbert Baker with sculpture by F V Blundstone.

Visit Passchendaele village and the Canadian memorial at Crest Farm.

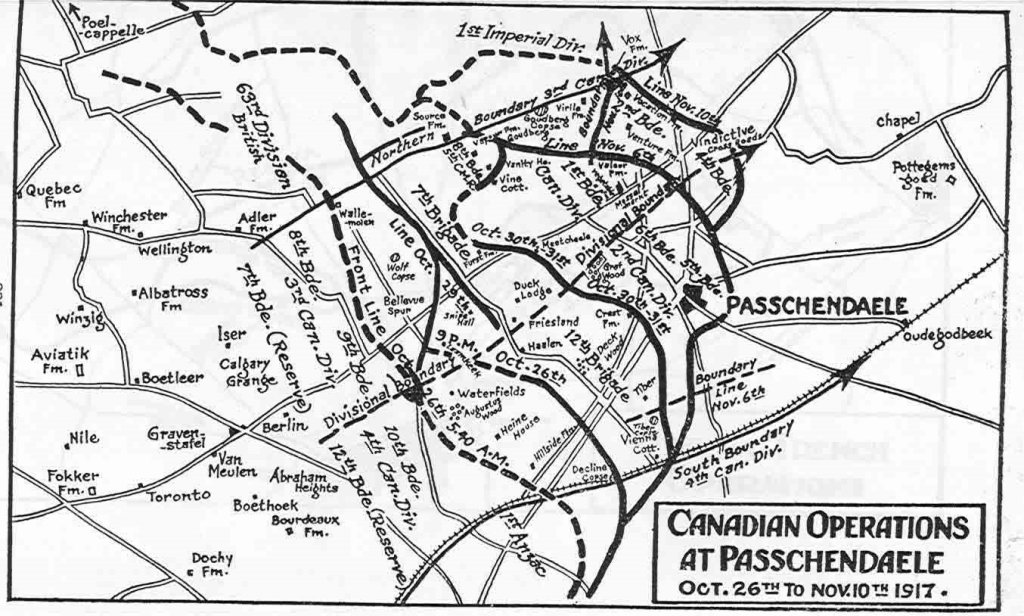

Having used his British divisions early in the battle followed by the Australian and New Zealand Divisions, Haig now turned to the Canadian Corps. Its commander, General Sir Arthur Currie, was reluctant to get involved in the bloodbath at Passchendaele after their endeavours at Vimy Ridge in April, but felt unable to refuse Haig’s request. He predicted that the planned attack would cost him 16,000 casualties.

The first attack, on 26th October, involved the 3rd and 4th Canadian Divisions. It had rained every day since 19th October, and the Canadian assault quickly bogged down. The 4th Division was eventually forced to retreat to within 100 yards of its starting point.

The attack was renewed on 30th October, with similar results. Once again the two Canadian divisions made small advances at heavy costs – the 78th Canadian Brigade lost half of its strength during the day. However, Canadian patrols did reach the village of Passchendaele, where they found the Germans preparing to retreat.

The village was finally captured by the 1st and 2nd Canadian Divisions on 6th November. The final action of the battle came on 10th November, although further bloody fighting continued into December, with an attack designed to straighten the line. Even after this final action, the Germans still held the northern end of the Passchendaele Ridge. Currie’s prediction was realised as the Canadians had suffered 15,634 casualties.

Visit the In Flanders Fields Museum, Zonnebeke.

Return to Ypres for dinner followed by the Last Post Ceremony at the Menin Gate 8pm.

TUESDAY 10TH JULY

Visit along the Menin Road – Hooge Crater, Polygon Wood etc.

Visit to the Aristocrat’s cemetery, Zillebeke.

Visit to Hill 60 and Caterpillar Crater.

Visit to the Bluff.

Visit to Spambroekmolen – Over view of the Battle of Messines 7th June 1917.

Visit Messines.

Visit Ploegsteert Wood – Scene of the 1914 Christmas Truce.

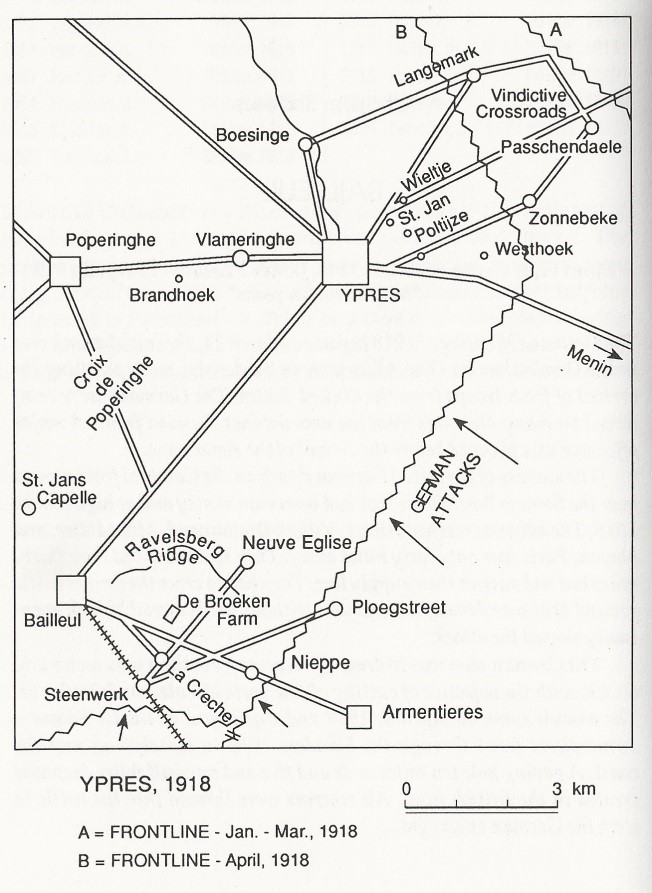

Visit Mon Noir/Bailleul – Location of Andrew Shaw’s capture as a POW in April 1918.

THE ROYAL NEWFOUNDLAND REGIMENT was going into reserve following a tour of front line duty in front of Ypres. They travelled to St. Jans ter Biezen on their way to join the rest of the 29th Division near Estaires, but there was to be no rest or billets. A critical situation had developed near Bailleul. The 34th Division had evacuated Armentieres on April 10. The Germans were advancing so quickly that it was likely this withdrawal would be cut off. The 25th Division had pulled back from Ploegsteert to the edge of Nieppe. The 88th Brigade was diverted to Bailleul under command of the 25th Division to secure the road from a threat caused by the Germans advancing from the south.

Near-Breakthrough by Germans April 10 1918. The Newfoundlanders were bussed to Bailleul and on to La Creche. A little after 4:00 P.M., April 10, 1918, they left the busses at La Creche, a village one and one-half miles from Bailleul. The Germans had occupied Steenwerck and were advancing towards Bailleul. C and D Companies went forward toward Steenwerck Station, coming under machine gun fire and suffering casualties. The low railway embankment made a good defensive position and the foremost troops of the Division were along one and one half miles of this track. They warded off German attacks during the day and dug in for the night, with the 40th Division on the left and the 34th Division on the right.

That night, the Newfoundlanders went into reserve, but were held in readiness for a counter-attack at any time. On April 11, the 88th Brigade came under the orders of the 34th Division. At midday, April 11, they were moved to De Broecken Farm, north of the Bailleul-Armentieres Road in order to protect the 88th Brigade from encirclement. At dusk, the 34th Division withdrew from Nieppe, back through the 88th Brigade.

April 12 2018, Crisis. April 12 was a day of crisis. The Germans had pushed the British from Estaires. The enemy were now in the rear of Bailleul.

The defensive position of the 34th Division held. The 88th Brigade was facing east on a front of 5000 yards from Steenwerck Station to the Bailleul Road behind Nieppe. The Royal Newfoundland Regiment was in the front line with the Hampshires on the right and the Monmouth Regt. on the left. At noon C Company was forward in the line, the other Companies were in support.

At 4:00pm a strong attack against the Monmouth Regiment started. That Regiment was ordered to hold its position astride the Bailleul Road, but was cut off and suffered over four hundred casualties. To cover the open flank, a platoon of C Company of the Royal Newfoundland Regiment, commanded by Lt. L. Moore, turned his front to face west and caught the advancing Germans in enfilade. The platoon held on stubbornly but was overwhelmed. Lt. Moore was wounded and taken prisoner. This heroic action allowed the rest of C Company to fall back in good order to the railway tracks north east of Steenwerck. Here, they were joined by A Company and the battalion HQ and stragglers from other units, to make a stand, commanded by Capt. G. Patterson. B and D Companies came up from reserve to join them. The Germans were halted by the determined fire of the Newfoundlanders.

That night, they withdrew to De Suele Crossroads, where the lateral road from Neuve Eglise meets the Bailleul Road. The Battalion was relieved by the Northumberland Regt. of the 34th Division. They retired to their reserve position, on call in case of a counter attack by the enemy.

Re-Newed Crisis April 13 2018. That call came the afternoon of April 13. At 5:00 P.M., a determined assault by the Germans had penetrated the British line and advanced along the De Broecken Road. This time, it was D Company’s chance to catch the Germans in the open. At 6.30 P.M., as the Germans advanced over open ground, D Company was in position to pour devastating fire into the advancing enemy. The rest of the Battalion joined D Company in this action. This stopped the enemy advance.

Later that day, the Regiment were ordered to Ravelberg Ridge to dig in at a previously selected position north from Bailleul to Crucifix Corner. They held this line on April 14.

On April 15, the Newfoundlanders marched back to Croix de Poperinghe (two miles north of Bailleul, on the slope of Mont Noir). Their stay in Nissen Huts here was less than twenty-four hours. The Germans had captured Bailleul and Ravelsberg Ridge. The Regiment went forward to dig with the rest of the 88th Brigade, about half way between Croix de Poperinghe and the ridge. While there were no German assaults during their stay in this line, there was heavy shelling but without serious loss.

Re-assignment and Relief. On April 21, the Battalion Was relieved by the 401 Regt. of the French 133 Division. They marched to billets near Steenvoorde and joined what remained of the 10% left out of battle. The next day, a short bus ride to Hondeghem, near Hazebrouck, reunited the 88th Brigade with the rest of the 29th Division.

The Royal Newfoundland Regiment had paid a high price for their part in stemming the German offensive. Casualties amounted to six officers and one hundred and seventy men. The fighting around Bailleul had left the Regiment far below strength. As no immediate reinforcements were available, the Regiment was taken out of the line.

(Extracted from Pilgrimage, with the kind permission of David Parsons.)

WEDNESDAY 11TH JULY

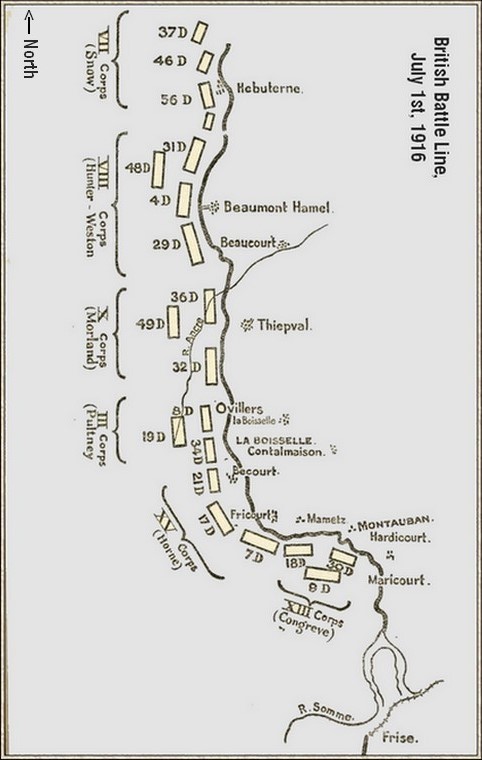

A tour of the Somme battlefield as it stood on 1st July 1916 and selected other dates.

Mametz Wood

Lochnagar Crater

Ovillers – The death of L/Cpl Jack D’Hooghe 3rd July 1916

Pozieres

Thiepval

Ulster Tower

Newfoundland Park

Beaumont Hamel – Sunken Road and Hawthorn Crater

Serre

Gommecourt

THURSDAY 12TH JULY

Monchy Le Preux – Andrew Shaw in action April 14 1917.

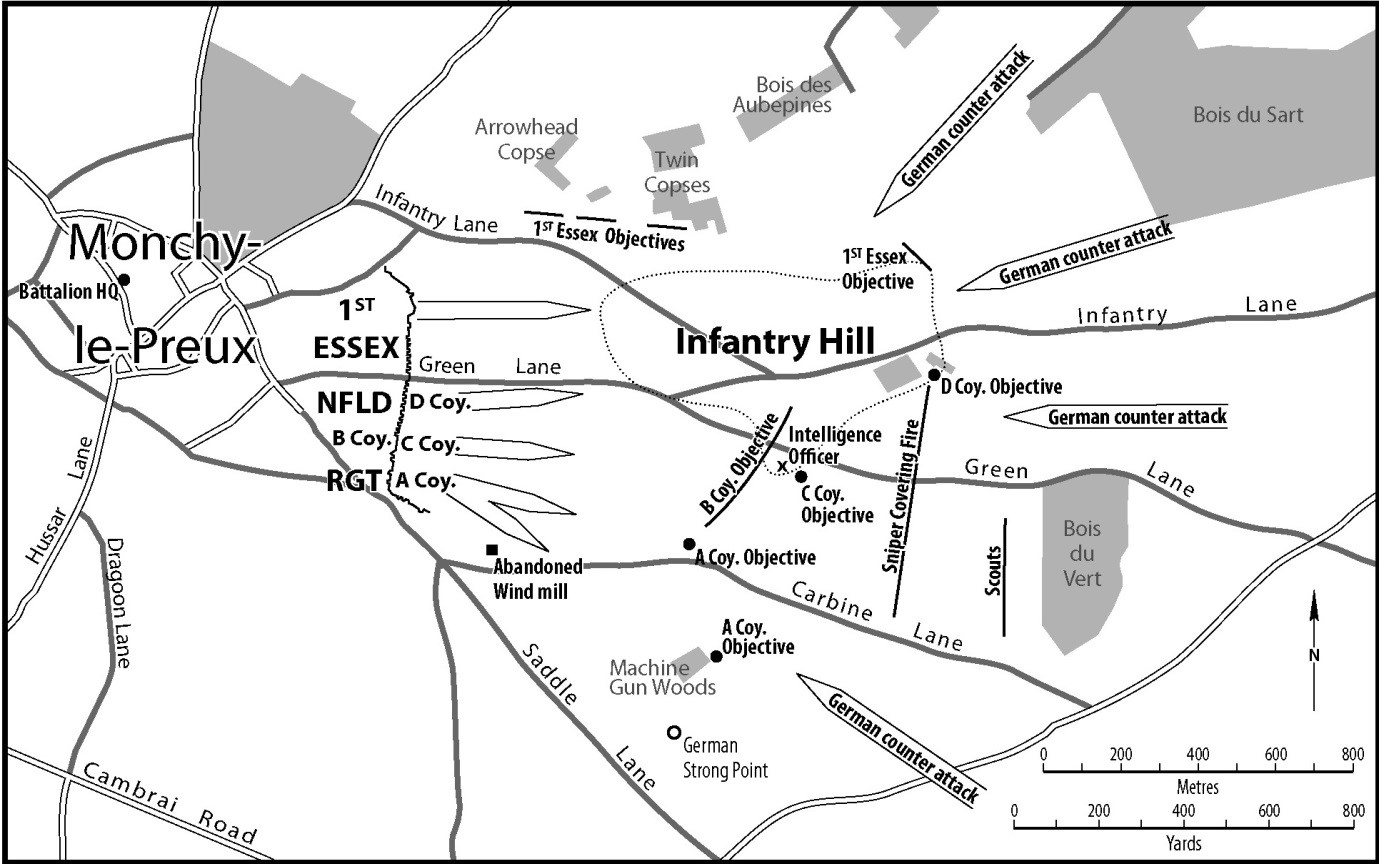

The Brigade’s task was to seize the enemy’s front line, Shrapnel Trench, and capture Infantry Hill, 1000 yards east of Monchy-le-Preux, pushing out detachments that would establish protective strong points across the front and along the flanks of the advance. The two-battalion attack was to be carried out by the 1st Essex Regiment (on the left) and the Newfoundland Regiment, under a creeping barrage.

The Newfoundland assaulting Companies were “D”, commanded by Captain Herbert Rendell, on the left, and “C”, under Captain Rex Rowsell on the right. Each would advance in two waves. Keeping direction posed no problem, for clearly visible from the Assembly Trench were the Bois du Vert, the north end of which gave “C” Company a bearing on which to advance, and on the left a small wood on Infantry Hill, which would guide “D” Company to its objective.

While the advance of the Essex Regiment would cover the Battalion’s left flank, there would be no corresponding external protection on the right. The important responsibility of securing this flank was given to “A” Company (Lieutenant I. G. Bemister). Earlier that night “A” Company had prepared a strongpoint, the first of four such platoon posts which it was called on to do, established along the Battalion’s southern flank. Of these the key point would be in a small copse called Machine Gun Wood, about 500 yards to the right of “C” Company’s objective, and some 700 yards in front of the Bois du Vert.

The Brigade order made provision for the Newfoundlanders’ subsequent advance once the initial objectives were attained. While the barrage stayed on the Bois du Vert the Regimental snipers and scouts, sixteen of each, would advance on the right of “B” Company under the Battalion Intelligence Officer Lieutenant Bert Holloway. They would attempt to get as far forward as possible and when the artillery fire lifted they would attempt to gain the near side of the wood. If they succeeded, “C” and “D” Companies would each rush a platoon forward to develop strong points on the eastern edge of the Bois du Vert. The snipers and scouts would again press forward, their progress being observed from “C” Company’s original strongpoint on Infantry Hill by the Intelligence Officer, who would, if he deemed it feasible, call on “B” Company to leapfrog further patrols forward. On the 88th Brigade’s left the Essex Regiment was charged with similarly sending out patrols.

The small force was to advance, unsupported on the flanks, against a position which when captured would form a salient, and hold it against possible counter-attack by incalculable numbers of the enemy.

At 0530 hrs a lone shell overhead signaled the start of the barrage. The leading waves of “C” and “D” Companies mounted the parapet and headed for their respective woodland objectives.

There was general agreement afterwards that the barrage had been deplorably thin, nothing like the solid curtain of fire laid down by the artillery at Gueudecourt. It failed to silence the enemy’s machine-guns, which almost immediately opened up across the whole front of the attack. The Newfoundlanders found Shrapnel Trench unoccupied, for the Germans had retired from it when the barrage opened. Within minutes the Germans replied to the British artillery with their own barrage. Monchy was heavily shelled, and as the Newfoundlanders advanced up the long slope of Infantry Hill, casualties came rapidly. On the left “D” Company, having overrun “A” German trench (Dale Trench) near the Battalion boundary attained its objective on the crest and began digging in. A number of Rendell’s men were seen advancing into the little wood beyond, but nothing more was heard of them. “C” Company’s leading wave, having lost thirty per cent of its men to the enemy fire, reached its assigned position on the hill, halting for the second wave to pass through. Captain Rowsell sent two Lewis guns to the crest to cover these latter platoons as they dug in on the far side; but although the guns were later heard firing at intervals, neither they nor the infantry of the second wave were seen again.

On the southern flank “A” Company captured the Windmill from a small group of Germans, and dropped off a platoon to entrench itself with a Lewis gun about 500 yards to the east. The remainder pushed forward to their objective at Machine Gun Wood and drove the Germans out. The plan to send scouts and snipers forward failed completely. Most of them became casualties to enemy shelling soon after the attack started, and Lieutenant Holloway was fatally hit when coming back to report that Bois du Vert could not be taken.

All this had occurred in the first ninety minutes of the action. At 7:20 a.m. Brigade Headquarters received a telephoned report from the Essex that they had captured their objective and were consolidating. There was no word from the Newfoundland Regiment. Runners returning with messages for Battalion Headquarters and wounded men trying to struggle back were shot down by snipers or machine-gun fire, reported to be coming from the valley to the south. Ten minutes after sending their success signal the Essex reported the enemy massing on their left front, in the vicinity of the Bois du Sart.

It was now about nine o’clock. Counter-attacked from three sides and with no sign of reinforcements, the survivors of the Newfoundlanders put up a desperate struggle against impossible odds. The forward platoons of the Newfoundlanders’ “D” Company were virtually surrounded by an estimated force of 500 Germans coming in from the Bois du Sart and another 200 from the Bois du Vert. They fought on until with the enemy only fifty yards away they were forced to surrender. About ten of them on the right of the line are reported to have made a break for it, but only one man got back to Monchy. It was the same grim story with “C” Company, where little knots held out here and there for a brief space until they were either killed or captured. The survivors of the platoons manning the strong points tried to retire, but very few escaped the small-arms fire coming from the southern flank. Farther back “A” Company’s platoon at the southern end of the start line temporarily halted with its fire two companies of Germans until an enemy shell knocked out its Lewis gun.

Back at Battalion Headquarters none of the messages entrusted to company runners had reached Lt Colonel Forbes-Robertson, and his only knowledge of the disaster that had befallen the Regiment came from the confused reports of excited and wounded survivors. Shortly after ten o’clock a wounded man of the Essex Regiment drifted in with word that all his battalion were either killed or captured. Forbes-Robertson at once sent his signalling officer, Lieutenant Kevin Keegan, forward to the Assembly Trench to reconnoitre the situation. Keegan was back in twenty minutes with alarming news. He reported that there was not a single unwounded Newfoundlander east of Monchy-le-Preux, and that he had seen some 200 to 300 Germans advancing in extended order less than a quarter of a mile away.

Captain K. J. Keegan, MC & Bar (courtesy Anthony McAllister)

It was a time for prompt action. Forbes-Robertson immediately ordered Regimental Sergeant-Major White to fall in the Headquarters staff and to collect every man that he could find. His intention was to hold off the German onslaught until reinforcements could come forward. With the telephone line to Brigade Headquarters broken, he sent Adjutant Raley back to report the critical situation. Then he led his little band, which numbered about 20 men, down the hill towards the enemy, picking their way between the broken houses of Monchy and arming themselves with weapons and ammunition from dead and wounded soldiers as they went. The enemy’s guns were still pounding the village, and a number were hit. But the intense shelling was encouraging evidence that the Germans had not yet entered Monchy.

At a house on the southeast corner of Monchy the Colonel halted his party. Climbing a ladder to a hole torn by a shell high in the wall he made a hasty reconnaissance. He could see the field-grey figures of the enemy tumbling into the jumping-off trench from which the Newfoundlanders had assaulted that morning. But midway between the trench and his point of observation was a well-banked hedge that seemed to offer a position from which the enemy might be checked. A quick rush across 100 yards of open garden plots, and the hedge was occupied. In this final dash, made in full view of the Germans, at least two men were shot down by the enemy’s machine-gun or rifle fire. In all, nine reached the protecting bank. There were two officers and seven other ranks, one of them a private of the Essex Regiment. In view of what followed it is fitting that their names be recorded here:

Lt.-Col. James Forbes-Robertson, Commanding Officer.

Lieut. Kevin J. Keegan, Signalling Officer.

Sgt. J. Ross Waterfield, Provost Sergeant.

Cpl. Charles Parsons, Signalling Corporal.

Lance-Cpl. Walter Pitcher, Provost Corporal.

Pte. Frederick Curran, Signaller.

Pte. Japheth Hounsell, Signaller.

Pte. Albert S. Rose, Battalion Runner.

Pte. V. M. Parsons, 1st Battalion, Essex Regiment.

To this list must be added the name of the Battalion Orderly Room Corporal, Cpl. John H. Hillier, of St. John’s, who was temporarily knocked out by a bursting shell during the rush forward, and crawled in from a shell hole some ninety minutes later to join the little group. They at once opened a series of bursts of rapid fire on the enemy, who believing themselves to be opposed by a powerful force, quickly went to ground. It was now 10:50 a.m. For the next four hours these ten resolute men “represented all that stood directly between the Germans and Monchy, one of the most vital positions on the whole battlefield.

Every bullet fired by the defenders was made to count. With the need to economize ammunition most of the Newfoundlanders’ firing was done at close range. They could see large numbers of enemy soldiers crossing the forward slopes of Infantry Hill, but they reserved their fire to pin down the Germans in the Assembly Trench and Shrapnel Trench and to catch small parties attempting to reinforce them. In the first two hours their bullets accounted for forty Germans, the CO’s deadly marksmanship being credited with three-quarters of these. And what was of greater significance, by picking off the scouts sent forward by the Germans to ascertain the strength of the force opposing them, the Newfoundlanders kept the enemy in ignorance of their pitifully weak numbers.

Shortly before two o’clock, when enemy snipers had become less active and only an occasional shell was falling on Monchy, Lt. Colonel Forbes-Robertson sent his runner, Pte. Rose, back to Brigade Headquarters with a report on the situation and an urgent request for reinforcements. He asked for artillery fire on Machine Gun Wood, which from the amount of movement in the vicinity appeared to be an enemy headquarters. Pte. Rose succeeded in delivering his message safely, and then, despite orders to the contrary, he again braved enemy bullets and shrapnel to make his way back and rejoin his comrades in their firing line. In response to the call for help Brigadier Cayley ordered up the Hampshires from his reserve. They reached the houses behind the Newfoundlanders at 2:45 p.m.; and at the same time the Divisional artillery began shelling Machine Gun Wood. Thanks to the heroic efforts of Forbes-Robertson and his men Monchy had indeed been saved.

So ended the fighting on April 14th. The enemy’s achievement had been to recover the ground captured by the Essex and the Newfoundlanders that morning and to cut those two battalions to pieces. But they had thrown away the opportunity to retake Monchy, and the end of the day found the position of the front line unchanged.

General de Lisle was not greatly exaggerating when he declared to the Newfoundlanders that if Monchy had been lost to the enemy on April 14th, 40,000 troops would have been required to retake it. Such is the measure of the achievement of the ten men who saved Monchy.

A caribou now proudly stands on a hill in Monchy facing the former German lines.

As soon as it was dark a platoon from the Hampshires came forward and relieved the Newfoundlanders. But there was still one more contribution to be made to the day’s heroism. Before they withdrew, Lieutenant Kevin Keegan went out with two of his men to bring in five wounded Newfoundlanders who were lying in a portion of the Assembly Trench unoccupied by the Germans. Back at Battalion Headquarters Forbes-Robertson collected another two dozen NCOs and men who had straggled in from the battle.

Later that day the Battalion counted its losses. The fatal casualties were exceeded only by the number of those who fell at Beaumont Hamel; and one-quarter of the Newfoundland officers and men who went into action at Monchy-le-Preux became prisoners of war. The Newfoundland losses incurred from April 12 to 15, 1917, based on existing information, total 460 all ranks. Seven officers and 159 other ranks were killed (or died of wounds), seven officers and 134 other ranks were wounded and three officers and 150 men were taken as prisoners of war. Of these 28 died from wounds or other causes while in captivity.

The Newfoundland Regiment remained in the Arras sector throughout April and despite depleted numbers found themselves holding a position at Les Fosses Farm on the road joining La Bergere with Monchy. The Second Battle of the Scarpe was scheduled to commence at 4:45AM on 23 April. While many of the Divisions reached their destination, a strong German counterattack late in the day reversed many of the gains the Allies had made. All day the Newfoundlanders were under continual shelling and machine gun fire but stubbornly held their positions. By June the Arras offensive had ended and the Newfoundland Regiment was moved south west to Bonneville. Its fighting strength was down to a mere 11 officers and 210 other ranks.

(http://www.rnfldr.ca/history.aspx?item=147)

Vimy Ridge – The Canadian Memorial Return to the UK via Eurotunnel.