1897-1979

My grandfather, always known as Jim, was born in August 1897 and was therefore, just aged 17 shortly after war was declared on the 4th August 1914.

Lord Kitchener as Secretary of State for War was one of the few men who believed that the war would be a long drawn out affair. He therefore appealed to the manhood of Britain to volunteer for overseas service. Jim attested on 1st September 1914 in Nottingham and swore to the Attesting Officer, Capt. J G Ashworth that he was 19 years and 5 months old!

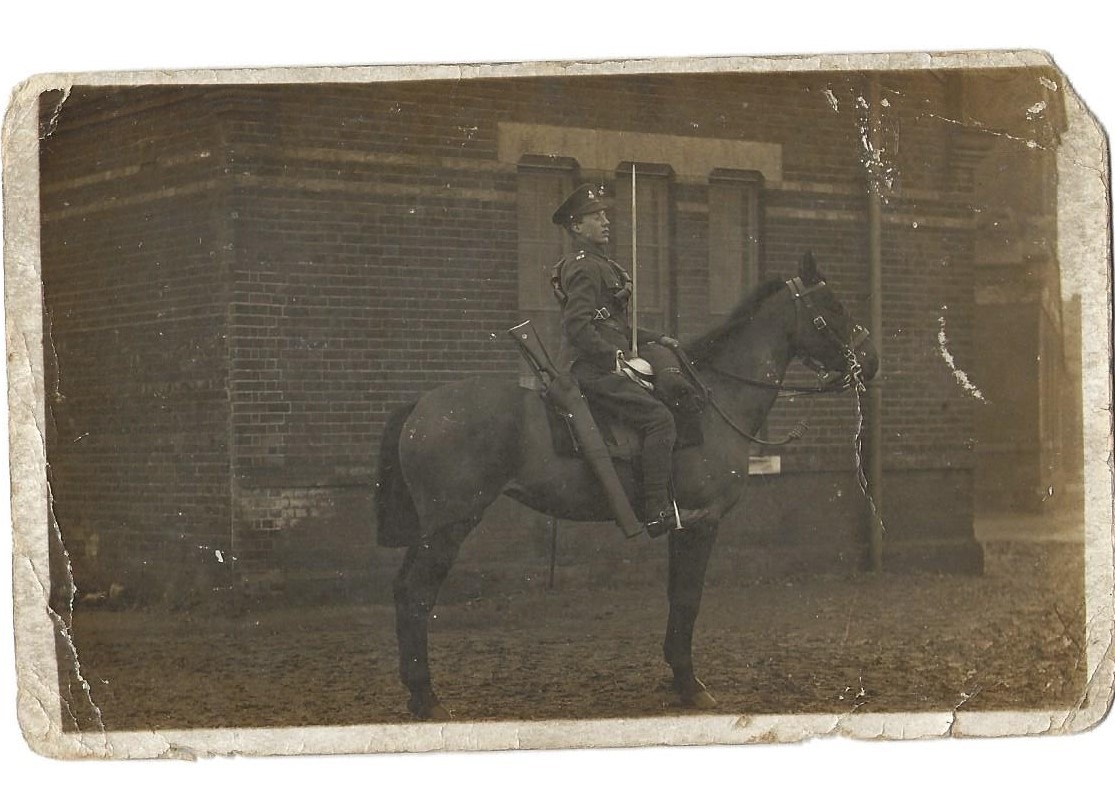

There is no story within my family that Jim in his young life had ever sat on a horse and it remains a mystery as to why he enlisted with the Hussars of the Line – although his older brother Jack did exactly the same and therefore, I surmise that the brothers joined up together.[1]

As is the way with tracing WW1 soldiers, Jim’s records have survived intact but his brother, Jack’s, papers have not. However, from letters and post cards that survive and are in my possession, Jack served with 8th Hussars and Jim found himself in Colchester with XX (20th) Hussars.

In pre-war days, it took 2 years to train a cavalryman and yet Jim received only 8 months training and was posted to his regiment arriving in Belgium via France on 19th May 1915 – thus becoming eligible for a 1915 Star to go with his BWM and VM which are all proudly in my possession.

The regimental history shows that XX Hussars were fighting as infantrymen in the trenches at this time but on ‘the night of the 21st [May 1915] we were relieved by infantry, and marched back to huts near Vlamertinghe.’[2] It appears likely that my grandfather thus missed the fighting around Hooge at this time but being in reserve did not mean they were safe. ‘At about 3-30am on the 24th [May 1915] we suddenly got the order to turn out. The air was full of gas. There had evidently been another gas attack east of Ypres.’[3]

XX Hussars formed part of the 2nd Cavalry Division reserve and occupied casements and dugouts in the ramparts at Ypres but often sent out digging parties at night to the front line to improve the trenches. Did Jim venture up to the front line as part of one of these parties? I shall never know but it must be likely and would have been quite an experience for a 17 year old.

On 31st May the regiment marched to billets at Zuytpeene west of Cassel and here they stayed until 5th August. Major Darling laments that for the next 2 months ‘the only part we took in the war was to send working parties to such places as Dickebusch to construct second and third lines of defence, and strong points behind the front.’[4]

‘On 6th August [1915] we moved a few miles to Wittes and Warne…’[5] Here the regiment was involved in training for the great cavalry breakthrough that was envisaged following the forthcoming Battle of Loos.

[1] Henry Taylor D’Hooghe always known as Jack served with 8th Hussars before being transferred as a Lance Corporal to 7 (Service) Suffolks in readiness for the Somme offensive of July 1916. Jack was killed on 3 July 1916 at Ovillers and is remembered on the Thiepval Memorial.

[2] Major J. C. Darling, 20th Hussars in the Great War (Published privately, 1923), p63

[3] Ibid, p63

[4] Ibid, p63

[5] Ibid, p64

This training included ‘practising swimming the horses over the Aire canal, in preparation for the grand pursuit after we should have gone through the mythical “Gap”’.[1] The soldiers were also being trained in the use of the first hand grenades to be available on the Western Front and this led to the end of Jim’s war.

XX Hussars left Warne on 21st September 1915 and moved south ready to take part in the Battle of Loos but on 20th September, just 4 months after his arrival at the front and during a bomb training session, Jim was wounded in the right eye by a grenade fragment. The battalion war diary notes on this date that ‘Captain Strickland and 5 men to hospital.’[2] The exact circumstances of the accident are not known but one can only assume a premature detonation occurred which wounded all 6 men.

My grandfather lived from the age of 18 to 82 with the loss of his right eye but like many men who served, he would not talk about his experiences and therefore, the next chapter of his story is pieced together with help of his medical and pension records which I have discovered.

Jim was initially treated at a field hospital before being admitted at the base hospital at Etaples on 22nd September. His casualty form states ‘Admitted G.[un] S. [hot] wound. R.[ight] eye. Severe. (Accidental.)’[3] He was then transferred back to Blighty via Boulogne on 7th October and admitted at the 2nd London General Hospital (Chelsea Eye Hospital.)

His first medical report dated November 15th 1915 states ‘Accidentally wounded by a bomb on Sept. 20th to Rt. Eye. Fragments struck the outer corner of the right eyelid, he can see shadows moving at a distance of 2 or 3 feet. X-Ray plate negative.’[4]

Jim remained in this hospital throughout the winter of 1915 (I have a photograph of the ward decorated with a Christmas tree!) but obviously did not respond to treatment and the decision was taken to remove his right eye. His medical record notes in late November 1915 that Jim’s wound was of a permanent nature and that he would never again be fit for active service – at 18 years and 3 months old.

In February 1916, Jim was admitted at the Nottingham Eye Infirmary, close to his home and on March 6th 1916 his records note that a ‘glass ball [was] implanted into the socket.’ April 8th, ‘Operation repeated’, May 8th ‘Glass ball removed.’ Obviously not all was well. [5]

He remained in hospital in Nottingham into 1917 and a further medical report was written on 7th February. It states; ‘This appears to be a case in which an attempt was made to save a severely injured eye; it was not excised till [sic] 10 weeks after the wound, with the result that when the eye was ultimately removed it left a chronically inflamed & oedematous socket. Various attempts have been made since to render the socket fit to carry an artificial eye, but without success. The socket is chiefly troublesome with open air.’ It is further noted that Jim was; ‘Permanently unfit. Could do munitions work, but would not do for outdoor employment.’[6]

[1] Darling, 20th Hussars, p64

[2] The National Archives (TNA) WO/95/1140

[3] TNA Forms/B 103/1

[4] TNA Medical Report on an Invalid. Army Form B 179. 7/MD/2372 – 2nd November 1915

[5] TNA Table II- Admissions to Hospital

[6] TNA Medical Report on an Invalid. Army Form B 179. 7/MD/2372 – 7th February 1917

Jim at the Nottingham Eye Infirmary middle of the back row without a hat between two Australians

My grandfather was officially discharged from the Army on 9th April 1917 under Kings Regulations Paragraph 392 (XVI) – No longer physically fit for active service. He was awarded the Silver War Badge and that is in my possession too. His Army reference states that he was a, ‘Sober, honest and reliable man. Discharged army to injuries received on active service.’[1]

Unfortunately, the next few years were not easy as the Pensions system downgraded his pension award from 60% which had been paid since July 1918. The loss of his eye was ultimately assessed as being worth a 50% pension and in April 1923, Jim appealed against this decision on the grounds that the award of the ‘50% pension is for the loss of sight of one eye [but] I have lost the right eye completely which causes facial disfigurement and I am dissatisfied with the assessment of the Board.’ He also stated that with the ‘Loss of right eye, socket still discharges and [I] cannot always wear the artificial eye and [I] have occasional headaches.’[2]

Nevertheless, the Tribunal ‘Disallowed [the appeal] and Affirmed’ the decision to reduce the pension award from 60% to 50%.

Jim sitting front right with his cap tipped over his missing eye.

[1] TNA Proceedings on Discharge Army Form B.268

[2] TNA Pensions Appeal Tribunal (Assessment)

Despite this setback, my grandfather went on to lead a full and worthwhile life; he learnt to drive and worked in the shop-fitting department for Boots the Chemist. He married my grandmother and had two children, Pam and my father John.

He died suddenly in 1979 but had sadly endured a lifetime of trouble with his eye for which he was still receiving treatment well into the 1960s. I only wish I had attempted to speak with him about his short time at the front when I had the opportunity.

Jim standing at the rear in the white shirt at the Nottingham Eye Infirmary

Jim’s brother Jack, killed at Ovillers, 3 July 1916 whilst serving with 7/Suffolks.